Challenge of Surviving a Brain Injury Without Diagnosis

Colliding Careers and Relationships after Brain Damage

By Gordon S. Johnson, Jr.

I suffered a moderate brain injury just before college graduation, a year before I went to law school. I was thrown from a car at expressway speed. When I woke up, I was surrounded by ambulance personnel. At the ER, they only evaluated me for a cervical injury. When the cervical x-ray was negative, I was discharged. This was in 1975. There was no CT scan. By not telling me I suffered a brain injury, which was clear to anyone at the scene, I was never given a warning of what was ahead.

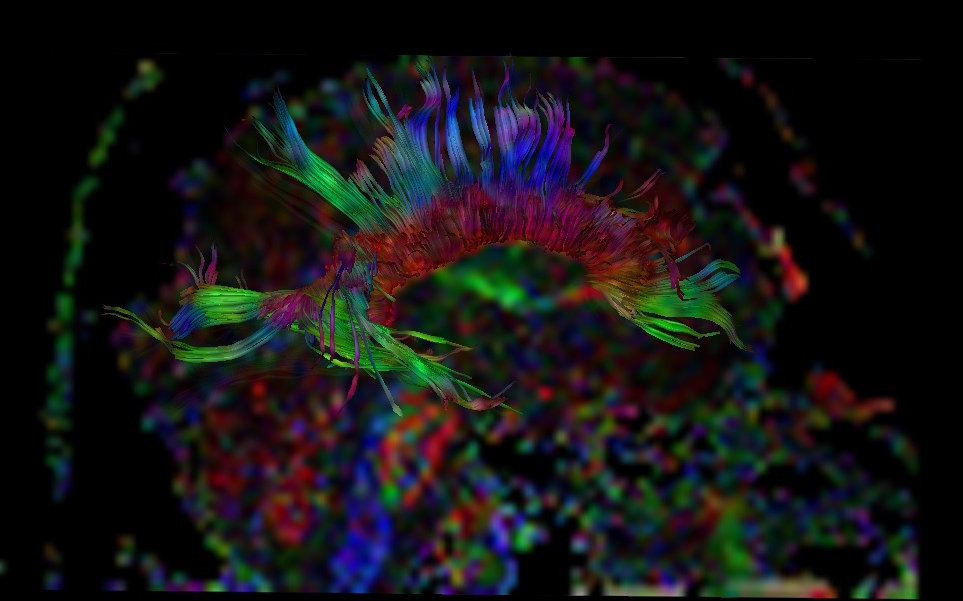

I didn’t discover how much pathology there was in my brain until an MRI done 38 years after the fact, in December of 2013.

If I had known I had a brain injury, would it have have held me back – robbed me of the confidence to have gone to law school. As neuropsychologists often say: don’t label the injured person with a brain injury.

Was I better off not knowing? Of course not. Am I a different person than I would have been? A snapshot of me at 60 is highly consistent with what my high school history teacher might have predicted. Yet that macro analysis skips over the ordeal of the year after my brain injury. Within a matter of a weeks, I gave up my chosen profession, lost the relationship which might have led to a long term marriage and became mired in the deepest kind of despair. Had a medical doctor or psychologist simply told me I had suffered a brain injury and that I needed treatment to help me get through those months, I would have avoided the devastating consequences.

I graduated from Northwestern University six weeks after my brain injury. I thought I was fine so I went off to start my career as a reporter on a small town newspaper in Leesburg, Florida. That job was not beyond my pre-injury ability. I was a graduate of the Medill School of Journalism and the Sports Editor of the Daily Northwestern. Despite that background, I was completely incapable of handling the pressure of a low level reporting job. I had the most difficulty initiating story ideas, especially under deadline pressure. On my second day in my career as a reporter, I got extraordinarily tired, lost confidence as to what to do next. I simply walked into the editor’s office and quit.

Surviving a Brain Injury Requires Loving Support

In the weeks between my car wreck and the end of my journalism career, I was volatile emotionally. I had been in a long term relationship with a wonderful woman who loved me but couldn’t comprehend my irrational jealousy and extraordinary dependency. If a doctor had offered both of us the simple explanation that the brain injury was making my life more difficult and stressful, she would not have given up on me. If a doctor had told me I wasn’t ready for the full time job, she wouldn’t have let me go. If she had insisted, I would have stayed and with her assistance, gotten back on my feet as a writer.

Sadly, at the time for the critical decision to take the job or stay with her, I had lost my ability to make those kind of choices. When the editor who offered me the job told me it was time to accept the job in Florida, I allowed him to choose for me.

Three months later my life as I knew it was gone. I had no career, no girlfriend, no respect from even my closest friends. I was shunned by the Northwestern University community where I had excelled. I was reduced to delivering newspapers for a paper that would no longer have my writing.

What saved me from further deterioration? By luck, on the last day before the deadline to take the Law School Admissions Test, I got the inspiration to become an attorney. Studying for the LSAT gave me a goal and focus. As my most significant problems were not cognitive, I was able to do well on the exam. Law school became a feasible plan. The LSAT gave me a bridge to a different outcome.

Yet a good score on the LSAT did not indicate recovery. I continued to struggle with initiative, motivation and relationships for the whole next year. I was still having problems my first semester in law school. But the discipline of law school and lots of aerobic exercise helped me get to a place that 18 months after my injury, my accidental recovery had reached the point that I was achieving at pre-injury levels.

Why Take a Chance on Accidental Recovery from Brain Injury?

No recovery should be left to chance. If I had gotten treatment, I could have saved my writing career. If a knowing and caring doctor had simply told the person who cared for me the most, why I was so different, she would have hung in there. Had someone told her – told me – that there was hope, my life would not have been abysmal for more than a year. By losing the relationship with a person who was my future wife, I lost my support network at a time I desperately needed it.

The significant risk factor after brain injury is not a cognitive failure, but neurobehavioral problems, as well as problems with mood. Those changes can put the survivor at odds with family, work and law enforcement. The cumulative total of everything melting down at once can push a person to suicide. Surviving a brain injury doesn’t happen if the brain injured person winds up dead or in prison. I got hope from the LSAT, but only just in time.

Brain injury changes lives, but it doesn’t have to doom a future. Based upon the long view, I have had a miracle recovery. But the chances of a surviving a brain injury are infinitely greater if one knows what it is they are recovering from. I could have started that recovery on day one. I shouldn’t have had to wait two generations for someone to tell me what happened to me.

For more on my struggles after my brain injury, click here.